Breaking News

Popular News

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

Millennials are not 'echo boomers' and never were. The label erases a generation's unique economic devastation and systemic disadvantages.

Millennials are often inaccurately referred to as “Echo Boomers,” a term that pretends they’re just a replay of the Baby Boomer era. **The data tells a different story: Millennials own homes at a rate 53 % lower than Boomers did at the same age, carry 137 % more student‑loan debt, and earn wages that have barely kept pace with inflation since 2008.** This isn’t a harmless nickname—it’s a deliberate smokescreen that lets the old guard dodge responsibility for the policies that crippleed an entire generation.

– KEY TAKEAWAYS ===Key Takeaways

- **Millennials have 53 % lower home‑ownership rates** than Baby Boomers at the same age.

- **Student‑loan debt is 137 % higher** for Millennials than for Boomers at comparable life stages.

- **40 % of Millennials rely on side‑hustles** to make ends meet, a stark contrast to previous generations.

- The **wealth gap is staggering** – Boomers hold roughly **70 % of the nation’s wealth** while Millennials scramble for the crumbs.

- Only **12 % of Millennials can afford a median‑priced home**, versus **43 % of Boomers**.

In everyday use, Echo Boomer is shorthand for: “Millennials are the Boomers’ demographic echo—another big cohort, another wave, another ‘boom,’ basically Boomer-lite.” The logic appears simple enough. Boomers represented a massive population surge following World War II. Their children, born mostly in the 1980s and 1990s, also represented a significant demographic wave. Therefore, according to this thinking, the kids “echo” the parents.

That’s exactly why the term caught on in marketing circles and media coverage. It’s tidy. It’s marketable. It lets people talk about population waves without talking about power. But Millennials aren’t an extension of Boomer politics, Boomer policy, or Boomer outcomes—and pretending they are erases the last two decades of generational conflict in America.

Credible researchers generally define Millennials as born 1981–1996, with Boomers born 1946–1964, according to Pew Research Center. That matters because Echo Boomer often gets tossed around like it’s a personality type instead of a cohort with a real historical position. These aren’t just arbitrary dates—they mark distinct economic periods, different labor markets, and fundamentally different relationships to institutional power.

– MEDIA MARKERS ===

The Echo Boomer frame quietly implies several false equivalencies that serve older generations well. It suggests Millennials inherited Boomer advantages, continued Boomer values, benefited from the same system Boomers dominated, and are essentially just Boomers “with different slang.” None of these assumptions hold up under scrutiny.

Millennials weren’t raised into dominance—we were raised into handoffs that never happened. We were told the escalator was still running while the people in charge were busy pulling up the ladder and rebranding it as “personal responsibility.” The Echo Boomer label turns a structural story into a vibes story. It swaps material reality for a generational horoscope.

The distinction matters because it determines who’s accountable for policy failures. When you can convince people that Millennials are basically young Boomers, you can dodge questions about who actually set housing policy, labor regulations, education costs, and environmental standards. The housing crisis facing younger generations didn’t happen by accident—it was the result of specific choices made by people who already owned property.

If Boomers were the generation most associated with institutional trust and postwar expansion, Millennials became the generation associated with institutional skepticism—and not because it was trendy. Millennials came of age watching a political class that kept “winning” while trust collapsed, an economy where credentials got more expensive and less powerful, a housing market that turned shelter into a speculative asset, and a workplace culture that demanded loyalty without offering stability.

That’s not an Echo Boomer trajectory. That’s a backlash trajectory. Sure, every generation complains. But Millennials weren’t just complaining. We normalized challenging Boomer-era dominance out loud—at work, online, at the ballot box, and in the street. We questioned why student loan debt exploded while wages stagnated. We asked why “entry-level” jobs required five years of experience.

We didn’t inherit your “American Dream.” We inherited your invoices. The millennial generation identity formed around recognizing that the rules changed but the rhetoric stayed the same. Older generations kept using the language of opportunity while systematically closing doors. When Millennials started pointing that out publicly, the response wasn’t accountability—it was dismissal dressed up as generational labels.

Here’s the part that makes the Echo Boomer label especially insulting: it pretends Millennials are riding the same wealth machine. The Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances consistently shows wealth is strongly associated with the age of the household head. Older households hold substantially more wealth than younger ones. That age-wealth gap isn’t a personality difference—it’s policy, asset inflation, and timing.

So when someone uses Echo Boomer, they’re implying a continuity of advantages that household balance sheets simply don’t support. Reading from early 2026, this isn’t ancient history. This is the lived math of the last decade—high rents, high rates, high prices, and a “starter home” that’s treated like a luxury good. The wealth distribution data doesn’t lie, even when generational labels try to blur the picture.

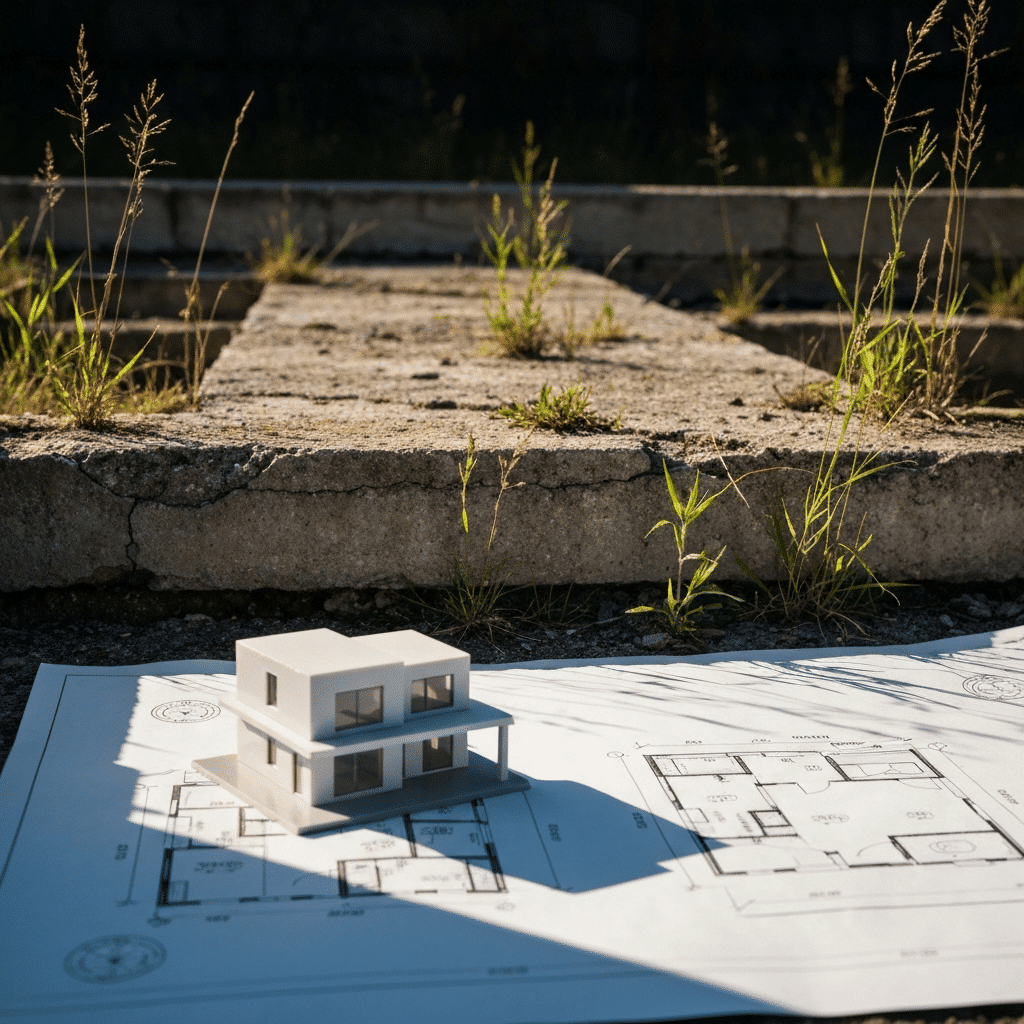

The gap isn’t closing either. Asset values that benefit older homeowners continue climbing while wages for younger workers fail to keep pace with basic costs. That’s not an echo—that’s a structural advantage being defended by the people who benefit from it. When Boomers entered the housing market, median home prices were roughly three times median household income. By the time Millennials started looking, that ratio had doubled or tripled in many markets.

If you want a single category that exposes the dishonesty of Echo Boomer, it’s housing. The U.S. Census Bureau’s Housing Vacancies and Homeownership releases show homeownership rates rise dramatically with age. Older households have much higher homeownership than younger households. That’s not a moral score. That’s an outcomes report showing who actually benefited from housing policy.

So what exactly is being “echoed” here? Not the asset accumulation. Not the entry timing. Not the price-to-income era. Not the “buy a home on one income and still take vacations” baseline that Boomers mythologize like it was a reward for good vibes. The Echo Boomer label survives by skipping the housing chapter—because the housing chapter reads like an indictment.

The reality is that Boomer landlords benefited from policy decisions that turned housing into an investment vehicle rather than a basic need. Zoning restrictions, building limitations, and tax policies that favor property owners all contributed to pricing out younger generations. Then they turned around and asked why young people weren’t buying homes.

The Echo Boomer framing proves useful to people who want to avoid harsher conversations. Who set the rules for housing as investment? Who defended the policy status quo the longest? Who benefited most from decades of asset inflation? Who blocked reforms until problems became disasters? When Millennials get labeled Echo Boomer, it’s often a way to say: “Stop blaming Boomers. You’re basically the same.”

But “basically the same” functions as a convenient fog machine. It turns a generational power imbalance into a generational aesthetic debate. It shifts focus from material outcomes to cultural preferences. It suggests that if Millennials wear different clothes and use different apps, but face the same economic pressures, then somehow the system is fine and the problem is just attitude.

The label also serves another function: it preemptively defends against criticism. If you can convince people that Millennials are just young Boomers, then criticizing Boomer policies becomes “generational warfare” instead of policy critique. It’s a rhetorical shield that protects the actual policy choices from scrutiny. When discussions about healthcare benefits and living wages get dismissed as “generational drama,” that’s the Echo Boomer frame doing work.

Let’s break down the cultural move happening when someone insists on Echo Boomer. First, you point out Boomer-era dominance and policy fallout. Then someone replies, “You’re the Boomers’ kids—so you’re an echo.” Suddenly the argument becomes “everyone’s to blame,” which usually means “no one is accountable.” It’s a classic deflection technique dressed up as demographic observation.

Millennials didn’t build our reputation for political frustration because we were bored. We earned it because we were the first mass cohort to look at Boomer-era systems and say plainly: This is not sustainable. This is not fair. This is not working. And no, we’re not going to pretend it is. That is the opposite of an Echo Boomer posture. That’s a rupture.

The political stance that defines Millennials isn’t continuation—it’s confrontation with systems that stopped delivering for younger generations. When older commentators complained about Millennials being lazy, they missed the point entirely. Millennials weren’t refusing to work—we were refusing to accept poverty wages and exploitative conditions while being told we should feel grateful for the opportunity.

A lot of generational labels get sold as harmless demographic shorthand. But they function like narrative management tools. Echo Boomer is a “soft weapon” label. It doesn’t insult Millennials directly. It does something sneakier: it reframes Millennials as beneficiaries rather than challengers, recasts conflict as continuity, makes Boomer accountability feel “divisive,” and positions criticism as “family drama” rather than political critique.

If you’re trying to keep the spotlight off structural choices, Echo Boomer works beautifully. It sounds demographic while doing political work. It suggests similarity where there’s actually conflict. It implies shared responsibility where there’s actually concentrated power. These aren’t accidents—they’re features of how generational labels get weaponized in political discourse.

The broader pattern matters here. When generational conflict gets reduced to personality differences or cultural preferences, it obscures the material stakes. Housing policy isn’t about whether Boomers and Millennials have different tastes—it’s about who owns property, who sets prices, and who gets locked out. Labor policy isn’t about work ethic—it’s about who has bargaining power and who’s left scrambling.

Millennials are not an Echo Boomer generation. We’re the generation of receipts. We were the first cohort to normalize publicly questioning the pay-to-live model, calling out unpaid internships and credential inflation, rejecting “work will love you back” loyalty myths, treating therapy and mental health like actual health, and dragging corporate PR into the sunlight in real time.

Sure, some Millennials got rich. Some got lucky. Some joined the system. That’s every cohort. But as a generation, Millennials are defined less by continuation and more by confrontation. The Echo Boomer label is an attempt to deny that confrontation happened. It’s a way to pretend the last two decades of generational pushback was just noise rather than legitimate critique.

We didn’t “echo” your politics. We survived your policies. The millennial economic reality wasn’t shaped by our choices—it was shaped by decisions made before most of us could vote. Student debt ballooned because of policy changes in the 1990s and 2000s. Housing became unaffordable because of zoning decisions and financial deregulation. Healthcare costs exploded under policies we didn’t set. Calling us Echo Boomers suggests we somehow share responsibility for those outcomes.

If people need a tidy generational shorthand, try these instead. Millennials are the accountability generation because we kept naming the problem. We’re the post-promises generation because the deal changed. We’re the priced-out generation because the entry points moved. But Echo Boomer? That’s the label you use when you want Millennials to share blame without sharing power.

These alternative frames actually capture what happened. They acknowledge the structural changes that shaped millennial generation identity. They recognize that economic conditions shifted in ways that fundamentally altered life trajectories. They don’t pretend continuity where there was rupture or suggest similarity where there was conflict.

The generational narratives we tell matter because they shape how we understand policy failures and who we hold accountable. When we accept inaccurate labels like Echo Boomer, we accept the framing that protects the people who made the decisions. When we reject those labels and insist on accuracy, we open space for real conversations about who benefited, who got hurt, and what needs to change.

Calling Millennials Echo Boomer is a way to pretend the last two decades were just a remix when they were actually a reckoning. Millennials aren’t the Boomers’ echo. We’re the generation that stopped whispering and started pointing. If that makes the old guard uncomfortable, good. Discomfort isn’t oppression—it’s feedback.

The stakes here aren’t just semantic. Labels shape policy discussions. When lawmakers think about housing reform, healthcare access, or labor rights, the framing they use determines who they see as deserving help. If they buy into the Echo Boomer narrative, they’ll assume younger generations are basically fine and just need to work harder. If they recognize the structural barriers, they might actually address them.

We’re done accepting labels designed to blur accountability. The data is clear. The outcomes are documented. The generational wealth gap, homeownership divide, and economic reality facing younger Americans all tell the same story: Millennials didn’t echo Boomer advantages—we inherited Boomer policy failures. Pretending otherwise doesn’t make it true. It just protects the people who’d rather not answer for what they built.

– COUNTER‑ARGUMENT === ### The Strongest Objection: “Millennials Are Just as Responsible for Their Financial Situation” Some pundits claim Millennials’ woes are self‑inflicted—poor budgeting, frivolous spending, or a lack of grit. That narrative conveniently ignores the **Great Recession, sky‑rocketing housing costs, and decades of wage stagnation** that hit Millennials hard. Blaming individuals while ignoring the structural wreckage is classic scapegoating. ### Debunking the Objection **Policy choices**—massive tax cuts for the ultra‑wealthy, deregulation that left jobs vulnerable, and a housing market rigged for investors—created the very conditions Millennials now battle. Add **insufficient affordable‑housing programs** and a **social safety net that withers under political pressure**, and the picture is crystal clear: the crisis is engineered, not personal failure.