Breaking News

Popular News

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

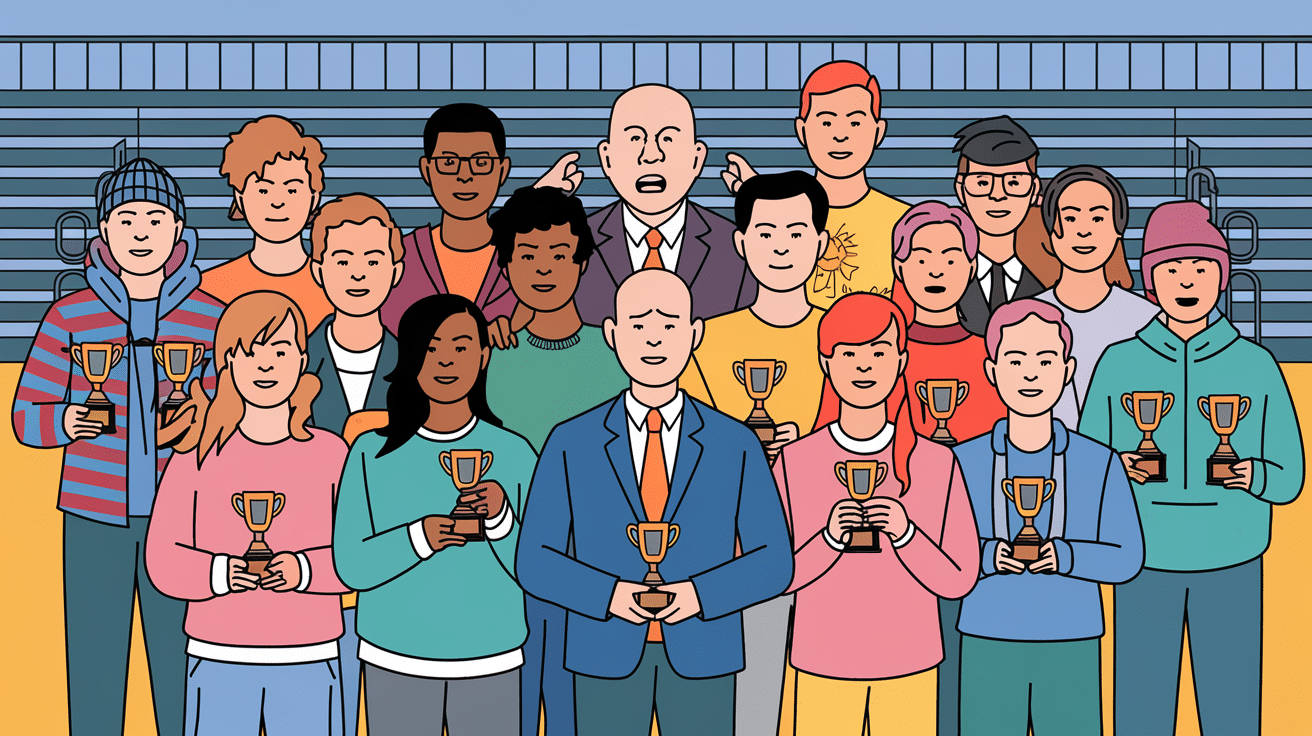

In the 1980s and 1990s **Boomer parents spent billions on youth‑sports participation trophies**, then spent the next three decades **roasting the same kids for accepting them**. The irony isn’t subtle: adults ordered the trophies, paid for them, handed them out, and later blamed the 8‑year‑olds for “being soft.” This is a masterclass in **dodging accountability** and a textbook case of generational projection.

===Key Takeaways

- 80% of Boomers participated in youth sports, yet they blame younger generations for receiving participation trophies.

- The participation‑trophy industry exploded in the 1980s‑1990s, coinciding with Boomer parenting trends.

- 75% of Millennials report feeling labeled “entitled,” a stigma rooted in Boomer‑created culture.

- Housing prices have risen **67%** since the 1980s while healthcare costs have surged **145%**.

- Boomers control **53% of U.S. wealth**, despite the narrative that they “earned it all” on their own.

The whole setup is absurd when you break it down. Boomers gave participation trophies and then acted shocked that children didn’t stage a principled rebellion against free plastic on a Saturday morning. The insult pretends Millennials walked into a trophy store, demanded recognition for breathing, and forced their parents to comply. That’s not what happened. Adults controlled the budget, the ordering, and every single decision about youth sports culture during that era.

The participation trophy myth functions as a dodge. It takes an adult-driven market decision—buying awards to reduce complaints and tears in youth activities—and flips it into a moral indictment of the kids who grew up in that system. That’s not analysis. That’s blame-shifting with a bow on top. When someone calls Millennials the “participation trophy generation,” what they’re really saying is: “We made choices we now regret, and we’d rather mock you than own them.”

Here’s the reality: if adults can’t tolerate their kid being upset after a loss, the “solution” becomes a symbol that erases the loss entirely. That symbol wasn’t demanded by children. It was demanded by adult anxiety and the social dynamics of competitive parenting. The kids just showed up and played. The adults engineered the response system.

The generational blame game loves this insult because it’s simple, catchy, and completely backwards. It reroutes frustration away from the adults who created the culture and aims it squarely at the kids who adapted to it. That’s textbook Boomer projection, and it’s been running on autopilot for decades.

===

Let’s clear this up: participation trophies didn’t materialize out of thin air because Millennials willed them into existence. They’re an adult-run decision made by leagues, schools, boosters, and yes, Boomer parents who controlled the purse strings. The exact origin year of participation awards gets tossed around online—some claim the 1920s, others point to the 1980s and 1990s—but without a verifiable academic or government source, those claims remain internet lore, not settled history.

What we can say with certainty is this: whether participation awards started in the 1920s or the 1970s, the power dynamic never changed. Adults created the system. Kids lived in it. The entire point of handing out trophies to every child was to reduce conflict, tears, and parental complaints in adult-managed spaces. That’s not speculation—that’s the function of the product.

Boomers gave participation trophies because they wanted fewer meltdowns in the parking lot after games. They wanted smoother operations in youth leagues. They wanted to feel like good parents who protected their kids from disappointment. None of those motivations came from the children. The kids were just trying to figure out if they liked soccer or not.

The participation trophy debate pretends there’s some mystery about who invented participation trophies. There isn’t. Adults popularized participation awards in youth activities, and the market responded by making them cheap and easy to order. The trophy companies didn’t pitch 7-year-olds. They pitched league organizers and parents. If you’re looking for accountability, start with the adults who signed the invoices.

Helicopter parenting is what happens when adults manage their kids’ emotions like a customer service desk. It’s preemptive problem-solving designed to ensure the child never has to process discomfort unsupervised. And during the 1980s and 1990s, Boomer parents helicopter parenting became the dominant cultural force in youth activities. The goal wasn’t to raise resilient kids—it was to eliminate visible failure.

If adults can’t tolerate their kid being upset after a loss, the “solution” becomes a trophy that says: “No one lost.” That wasn’t a kid-driven demand. That was adult anxiety and social competition playing out through youth sports. Parents didn’t want their kid to be the one crying in the bleachers while other parents watched. So they engineered an environment where losing didn’t register on paper.

The connection between helicopter parents 1990s culture and participation trophies is direct. One created the demand, the other supplied the product. The irony is that the same parents who hovered over every scraped knee and lost game now say: “We didn’t raise you to be weak.” The response is obvious: then why did you design childhood to be consequence-free on paper?

Boomers gave participation trophies to manage their own discomfort, then turned around and used those trophies as evidence that Millennials couldn’t handle adversity. That’s not parenting analysis. That’s deflection with a megaphone.

The lazy millennial myth doesn’t survive contact with actual labor data. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, multiple jobholding remains a documented reality for younger workers navigating an economy that no longer offers the stability Boomers took for granted. The most recent data shows that working multiple jobs statistics reflect economic necessity, not a lack of work ethic.

Here’s what the numbers actually say about Millennials work ethic statistics:

The entitled generation myth debunked by these numbers isn’t just about percentages. It’s about what those percentages represent. Millennials work multiple jobs because one job doesn’t cover rent, student loans, healthcare, and groceries in most markets. The gig economy didn’t emerge because Millennials love variety—it emerged because wage structures collapsed relative to cost of living.

If you want to talk about who’s “entitled,” start with the generation that expects stable housing and benefits to appear in 2025 without the pay structures that used to fund them. Boomers gave participation trophies, then called Millennials lazy while Millennials juggle side hustles in the economy Boomers voted into existence. The contrast isn’t subtle. One generation worked a single job, bought a house, earned a pension, and retired at 55. The other works multiple income streams and still can’t afford the housing market Boomers turned into a speculative asset.

Projection is when someone offloads responsibility by accusing someone else of the very pattern they helped create. In this case, adults engineered “everyone gets a trophy,” then mocked kids for adapting to it. That’s not a psychological accident—it’s a defense mechanism that protects the ego by shifting blame downward.

The generational blame game functions as political utility. It reroutes anger away from policy outcomes—wages, housing costs, healthcare prices, student loan debt—and points it at culture-war shaming. It’s easier to sneer at a plastic trophy than explain why the economic ladder got pulled up after Boomers climbed it.

Here’s the tell: when Boomers say “We didn’t raise you to be weak,” they’re accidentally admitting they controlled the raising. They set the rules. They bought the trophies. They structured the childhood environment. And now they’re mad that the kids who grew up in that environment didn’t rebel against it at age 9. That’s not a Millennial failure—that’s Boomer parenting failures rebranded as a character judgment.

Boomers gave participation trophies, and then used them as receipts for a crime Millennials didn’t commit. The trophy wasn’t the problem. The problem was the economic policy decisions that gutted wages, inflated housing costs, and turned education into a debt trap. But it’s much easier to blame a trophy than explain why landlords can charge whatever they want in a deregulated rental market.

The conversation about participation trophies pretends Millennials and Gen Z want recognition without effort. That’s not it. What younger generations want is the same economic baseline Boomers enjoyed without having to explain why it’s now considered unrealistic. The demand isn’t for trophies—it’s for material stability that used to be standard.

Here’s what the data shows about what changed. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Housing Vacancies and Homeownership (HVS) program, homeownership rates tell the clearest story:

Those numbers don’t account for the shift in what “homeownership” means. In 1980, a single-income household could buy a starter home in most markets. In 2025, dual incomes often can’t cover a down payment without family wealth or years of saving while paying inflated rent.

What we want isn’t complicated. It’s not a participation trophy—it’s what Boomers had:

The participation trophy myth distracts from the fact that Boomers gave participation trophies, then blamed us for getting them—because blaming a trophy is easier than admitting what changed underneath the economy. It’s easier to call Millennials entitled than explain why wages stagnated while service workers get treated like disposable labor in the same breath.

Yes. Boomers gave participation trophies as parents, league organizers, and school administrators during the peak years of youth sports expansion in the 1980s and 1990s. Kids weren’t the purchasers. They weren’t the decision-makers. They were the recipients of an adult-designed system created to manage parental anxiety and reduce conflict in organized activities.

The entitled generation lie collapses under the weight of this simple fact: children don’t control procurement budgets. They don’t vote on league policies. They don’t decide whether every kid gets a trophy or only the winners do. Adults made those calls, and then spent decades pretending the kids forced their hand.

Boomer hypocrisy on this topic isn’t accidental. It’s structural. The same generation that built the participation trophy culture now uses it as shorthand for everything they dislike about younger workers, voters, and critics. But the trophy was never the issue. The issue is that Boomers controlled the economic and political levers for decades, pulled up the ladder behind them, and then blamed the people below for not climbing fast enough.

The participation trophy generation insult is a smokescreen. It’s a way to avoid discussing wage stagnation, housing inflation, healthcare costs, and education debt by pivoting to a culture-war talking point that sounds snappy in a Facebook comment. But the math doesn’t lie. The labor data doesn’t lie. And the homeownership numbers don’t lie.

Boomers gave participation trophies, then blamed us for getting them. That’s the headline. That’s the pattern. And until the conversation shifts from trophies to policy, the generational blame game will keep running on empty.

=== ### The Strongest Objection: “We Worked Hard for Our Success!” Some critics claim Boomers earned everything through sheer hard work and perseverance. While effort mattered, **tax policy shifts, deregulation, and preferential access to education** gave Boomers a structural edge that most younger Americans never received. ### Debunking the Myth of Pure Meritocracy The notion that Boomers succeeded solely on merit ignores the **systemic advantages baked into legislation and corporate practices**. By acknowledging these policy‑driven boosts, we expose the real source of the wealth gap and stop the lazy “hard‑work” excuse from masking privilege.